How healthy is your neighborhood?

A new way to understand urban well-being

Cities are more than just buildings. They shape how we live, feel, and connect. A healthy city offers clean air, safe transportation, green spaces, and opportunities for social interaction. Yet, as urban areas expand, these qualities come under pressure.

By 2050, nearly 70% of the world’s population will live in cities, facing increased noise, pollution, inequality, and stress.

Improve health

To address these challenges, the municipality of Eindhoven launched the Healthy Living Area project, aiming to improve health in neighborhoods. However, they encountered a key obstacle: existing tools focused either on hard data or personal experiences — rarely both. What was needed was a method that could integrate objective indicators with the lived experiences of residents.

In collaboration with the municipality, Eindhoven Engine hosted the EngD project of Golnoosh Sabahifard, embodying its core philosophy: deeply understand the problem before jumping to solutions. A systems overview was essential, beginning with a systems dynamics sketch — the foundation for a model that could later support policy scenarios. Crucially, the project wasn’t done for the people, but with them. Stakeholders were involved in co-creating and validating the systems map, ensuring it reflected real experiences. These principles — co-creation, systems thinking, and problem understanding — are central to Eindhoven Engine’s approach to innovative solutions.

A new approach: Combining data with daily life

With a background in architecture and built environment, Golnoosh brought a systems-thinking mindset to the project. She combined systems dynamics modeling with citizen participation, using the Vensim platform to build a model based on eight criteria — four social and four environmental — already used by the municipality:

Social indicators:

- Socioeconomic status (SES)

- Loneliness

- Stress

- Years in good perceived health

Environmental indicators:

- Green space

- Noise levels

- Distance to facilities

- Population density

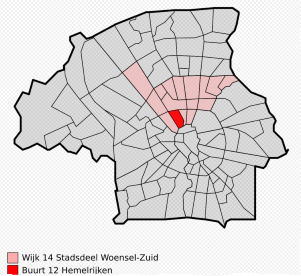

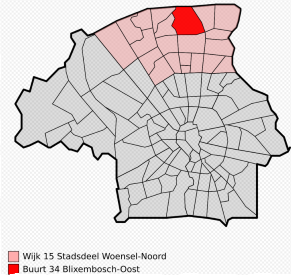

These criteria were applied to two neighborhoods: Hemelrijken and Blixembosch-Oost. The model visualized how these factors interact, enabling comparison and scenario testing. But numbers alone weren’t enough. To capture residents’ perspectives, Golnoosh used the Repertory Grid technique. Participants compared criteria in triads — for example, stress, green space, and noise — and explained which two felt similar and why. This revealed personal constructs like “quiet vs noisy” or “stressful vs calm.” Residents then rated all criteria, adding depth and nuance to the model.

Neighborhood-specific strategy

The findings were revealing. In Hemelrijken, low SES and high stress emerged as the strongest negative drivers of health. Green space and noise were key environmental concerns. Residents confirmed these insights, emphasizing stress, noise, and crowding as major issues. They prioritized solutions such as stress relief, affordable housing, and long-term health support.

In contrast, Blixembosch-Oost presented a different picture. Residents focused more on long-term health, SES, and green space. Loneliness and distance to facilities were more prominent concerns, reflecting the suburban layout. While noise and stress were present, they weren’t central. Residents valued green space and lifestyle health, viewing affordability and density as moderate issues.

These differences highlight a crucial lesson: urban health strategies must be neighborhood-specific. What works in one area may not apply in another. A one-size-fits-all approach simply doesn’t work.

Based on the findings, Golnoosh proposed tailored solutions:

- For Hemelrijken: pocket parks, green roofs, noise reduction measures, affordable housing, and community events to relieve stress and foster belonging

- For Blixembosch-Oost: preserving green infrastructure, health awareness programs, noise buffers, and inclusive community activities

Two additional insights emerged. First, urban health is shaped not just by data, but by people’s lived experiences. Residents often described health in personal terms, such as ‘quiet vs noisy’ or ‘stressful vs calm’. Second, co-creation is essential: involving residents leads to more grounded and accepted solutions.

Finding solutions is easy — once you truly understand the problem.

The next phase

The project didn’t end there. A new team member, Veron Afonso, joined to expand the systems dynamics simulation, bringing an IT perspective. The next phase involves returning to residents for validation and scenario building, continuing the cycle of co-creation and refinement.

This project exemplifies how diverse expertise, citizen involvement, and systems thinking can lead to meaningful urban innovation. As Golnoosh’s work shows, understanding the problem deeply is the key to designing healthier cities. Once the real challenges are clear, solutions follow naturally.